Omphaloskepsis Blog

The Attraction of Aversion: Why we can't look away

Jul 26, 2015

Averse Attractions: Why we can't look away

I'm delighted to see that the discussion about the grotesque is in the mainstream again. I wrote about this several years ago: The psychological attraction of gore

Recently the Huffington Post started a discussion about the draw of and accessability to horrific and gory images, memes, and internet clips. Why we can't stop watching disgusting videos:

"Disgust actually acted like a cognitive interrupt. You forgot what you saw before that because the disgusting stuff became the only salient thing in that message," Rubenking explained.

Coupled with that is "the urge and the need to tell someone else" about what you've seen, said Know Your Meme editor Brad Kim, who appeared on the HuffPost Live segment along with Rubenking.┬Ā

"To borrow the words of the Internet axiom, 'What has been seen cannot be unseen. But what has not yet been seen but [is] discouraged to see, must be seen,'" Kim said. "This is kind of the underlying psychology that drives people to say, 'Oh yeah, I want to see and I want to know how disgusted I can get.'"┬Ā

And there actually is a cognitive benefit to watching and sharing extreme content.

"Part of that can be explained by inherently being humans and wanting to learn from what is disgusting, so you don't become the disgusting dead body or you don't eat the wrong thing," Rubenking said. "There is something very cool and social about disgust responses that we don't see in regards to all different types of memes."

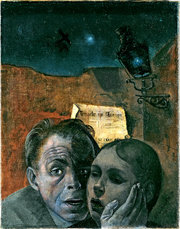

From top: Rodin-Gates of Hell 1917,┬ĀLouise Bourgeois-Maman 1996, Felix Nussbaum-Fear 1941, Isaac Cordal-Cement Eclipses, Artemisia Genileschi-Judith Beaheading 1614, Hieronymous Bosch-Harrowing of Hell c:1500

Great art makes us uncomfortable because it deals with the most basic, universal aspects of the human experience. It establishes a connection between the artist and the viewer based on shared emotions and common understandings of feelings such as happiness, anger, and pain. It takes these fragments of the human psyche and reflects back who and what we are. It triggers our past, our sense memory, and how we come to understand the world in which we exist. Great art drills down into the universal and uncomfortable ontological questions that have occupied humankind for generations. Is this real? Where is consciousness?

2010 CoCA press release:

[sic] the artistŌĆÖs radical project is immediately apparent in her ŌĆ£accident seriesŌĆØ in which a single figure is in the process of a horrific (and usually grotesquely bloody) accident with a chainsaw, shotgun, axe or similar tools and weapons. Her handling of the paint matches the situationŌĆÖs goriness ŌĆō melting bodies tossing explosive splatters of blood. Often, her subjects seem not yet to be aware of the violence they have perpetrated on themselves: The viewer plays the role of the witness much as he might watch a horror movie ŌĆō completely aware of the violence and agony that awaits the victimŌĆÖs realization.

VrijmoetŌĆÖs subject, however, is less the gore than the moment the gore marks: A moment of waking, of a new consciousness, of self-awareness. Her subject is trauma itself ŌĆō the word coming from the German for ŌĆ£dream.ŌĆØ The accidents mark the rest of the victimŌĆÖs life, whether it is merely to be a few more seconds or to lived from then on without an arm, a leg or an eye ŌĆō or with deep physical and psychological scars.

The idea of waking is what draws VrijmoetŌĆÖs main bodies of work together.

This is not a phenomena new to the age of connectivity. Afterall, in 1757 Edmond Burke wrote "Astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror." -Edmund Burke, On the Sublime

Goya, Saturn devouring his children

In his CoCA catalog essay titled: The Accidental Purist: Kate Vrijmoet and the American Sublime Art Critic Dan Kany writes:

There is no denying one of the most historically important and powerful painters of Western culture was Fransciso Goya. Late in life and at the peak of his powers, Goya painted directly onto the wall of his home a series of paintings known as the Black Paintings. The most famous of these is Saturn Devouring his Son, after the Roman god who ate his children in a desperate attempt to ward off the prophecy that one would ultimately overthrow him.

It is arguably the most brutal painting to scale the heights of the canon of Western art history. On a sheer black background, a wide-eyed and maniacally desperate Saturn ŌĆō a naked giant ŌĆō bites off his sonŌĆÖs left forearm having already devoured his head and right arm. The naked (adult) body hangs limp though squeezed by the madness of his terrified father. The body could be that of any viewer.

What makes this painting so terrifying is that the viewer identifies with the decapitated body. It provides scale in the face of the insanely violent monster. It lets us see ourselves in the image.

ItŌĆÖs worth asking why such a painting is so powerful, so captivating and so compelling. The answer goes beyond sympathy for this victim of cannibalistic filicide. We ask ourselves what kind of person would paint this picture. Who, moreover, would paint this for permanent display in his own dining room?

The paintings of Kate VrijmoetŌĆÖs Accident series raise similar questions in the face of more contemporary incidents of raucous blood and gore.

In a recent Salon article on why we can't look away: "One anonymous internet user said, ŌĆśYou almost canŌĆÖt believe that a group of people could be so pitiless as to carry out something so cruel and bestial, and you need to have it con?rmed . . . Watching them evokes a mixture of emotions ŌĆō mainly distress at the obvious fear and suffering of the victim, but also revul┬Łsion at the gore, and anger against the perpetrators.ŌĆÖ"

Eric Wilson wrote a book about why we can't look away. Everyone Loves a Good Train Wreck examines our fascination with darkness and evil and discusses our curiosity about death asking the question: What makes these spectacles so irresistible?

These are my creepy little kids at an opening of my zombie paintings in 2011. I love their willingness to fully embodied the spirit of the whole event.

The artist gives us madness, death and suffering and asks us how we plan to come to terms with what sheŌĆÖs shown us. ThatŌĆÖs what makes art memorable. ThatŌĆÖs what distinguishes Neel, Chicago and Emin from artists who donŌĆÖt understand the power she has to connect us. ItŌĆÖs what marks the work of Sexton and Plath as time-less. And what I hope will set me apart as well.

Death is one of two universal experiences. In large part, my work deals with birth and death and our ability to be conscious and present in between the two. I am fascinated by our relationships to the world and each other, and how they affect our beliefs about our existence.

MENU

MENU